Bridging the gap

by Sara Veale, Future Spaces Foundation

2019

A resonant aspect of the loneliness debate is reconciling the prevalence of this issue with the diversity of its expression. Urban loneliness is a global concern, but it’s not a monolith; examples in practice vary wildly around the world depending on the environment and people involved.

In megacities like Tokyo and Mumbai, loneliness is intertwined with rapid, alienating bursts of development that fragment landscapes citizens once knew. Residents of mid-size North American metropolises, meanwhile, are prone to a loneliness brought on by suburban sprawl, which generally eschews walkable amenities and other building blocks for tight-knit communities. There are common threads between these places – including the ubiquity of social media and other products of globalisation – but their individual terrains and populations form distinct topographies for mental health.

As built environment professionals, it’s our responsibility to examine the unique settings of the locations we work in. This is key to bridging the gap between mere proximity and meaningful togetherness in schemes intended to tackle loneliness, whether they’re site-specific interventions or broad-strokes blueprints for change.

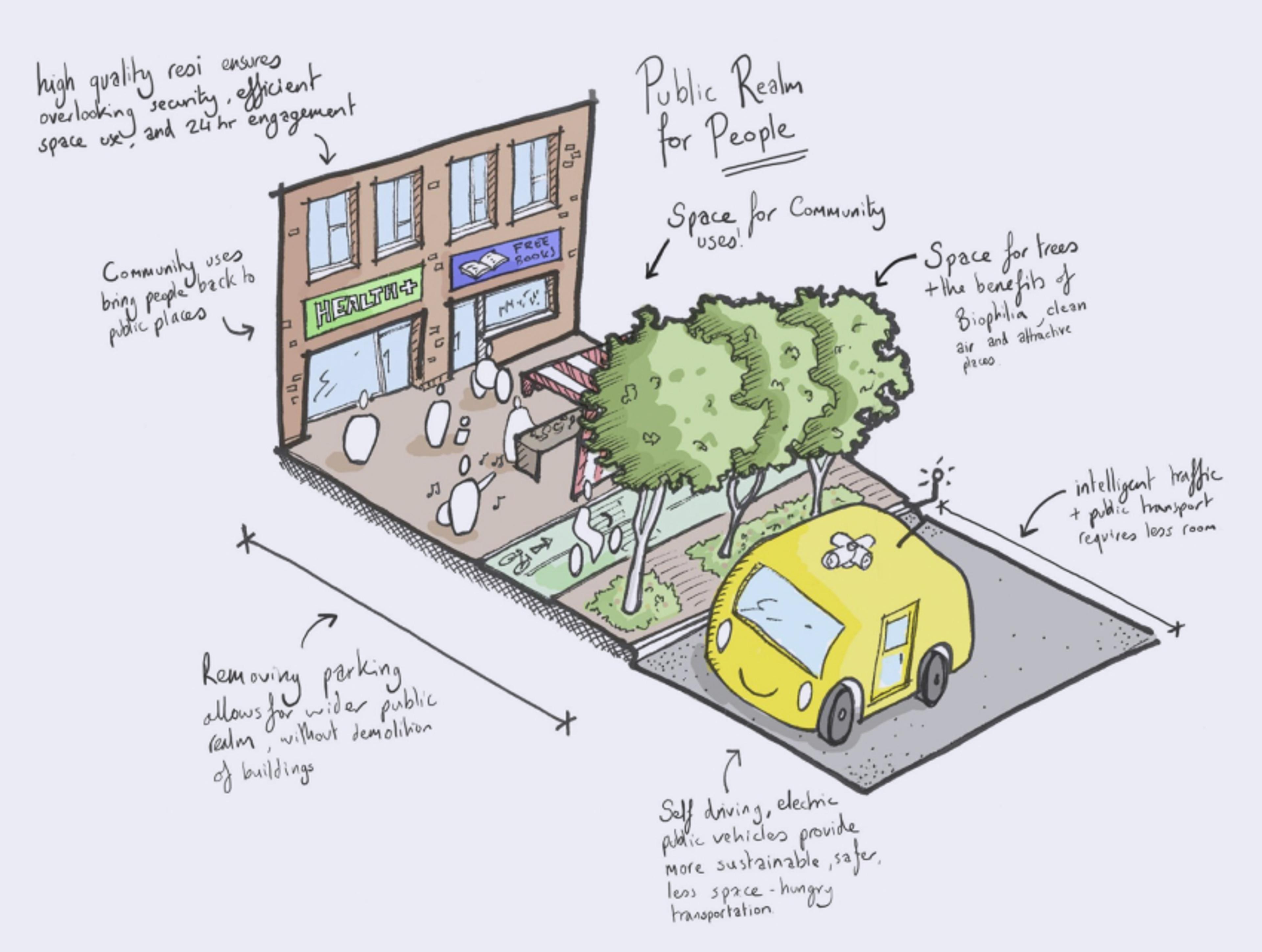

At Make, we have studios in London, Sydney and Hong Kong, with live projects across the globe. Some of the considerations our designers face in the UK include social stratification and the so-called death of the high street. These coalesce in efforts to address loneliness in British cities, where public spaces risk injudicious privatisation. There’s a growing appetite to repurpose space for community use across the country, but it takes a considered planning approach. With our Hornsey Town Hall project, for example, Make is restoring an historic civic building to create a new neighbourhood arts hub – a scheme made possible through a strategic deal between the local council and a private developer.

In Australia, there are low-density, car-reliant suburbs to contend with, which often miss out on the social opportunities a neighbourhood can reap when housing and public spaces mingle. One approach designers are taking to strengthen social ties here is diversifying the use of business districts, offering valuable communal spaces to workers and visitors who might not have these at home. Make’s renovation of a celebrated sandstone building in Sydney’s CBD, for example, includes reinstating the adjacent public realm as a vibrant, inviting city square.

In Hong Kong, it’s extreme density that’s exacerbating loneliness, with homes packed so tightly that many people don’t have space to invite friends or family over. This is compounded by the region’s low concentration of accessible urban green space, which leaves few places to comfortably socialise for free. One architectural tack is improving residential design to offer better connections to nature and more chances for social interaction. Views and natural light play a major role, as do shared social amenities – features that can be found in Make’s Luna and Dunbar Place developments, both of which strive to foster a community spirit that’s often lost in high-density living.

None of these examples solve the problem of loneliness on their own, of course. But as actors in an industry increasingly attuned to the human costs of the issue, architects can play a vital role in creating opportunities for meaningful togetherness around the world.

This post was extracted from our Kinship in the City report.