Greener cities

by Frances Gannon, Make Architects

2015

The value of green

Describing his vision of the ‘Town-Country’ Garden City, Ebenezer Howard said: “Human society and the beauty of nature are meant to be enjoyed together.” This chimes with contemporary research relating a connection to nature to people’s psychological state and social cohesion. Close proximity to nature has been linked to healthier babies, less lonely and depressed seniors, and more productive workers. Dutch researchers have investigated the value of ‘Vitamin G’, the effect of green space in the living environment on health, well-being and social safety. The Biophilia and Biourbanism movements are strengthening, asserting that humans seek connections with and gain positive feelings from ‘the rest of life’, including the whole of the natural world, be it plants, animals or the weather.

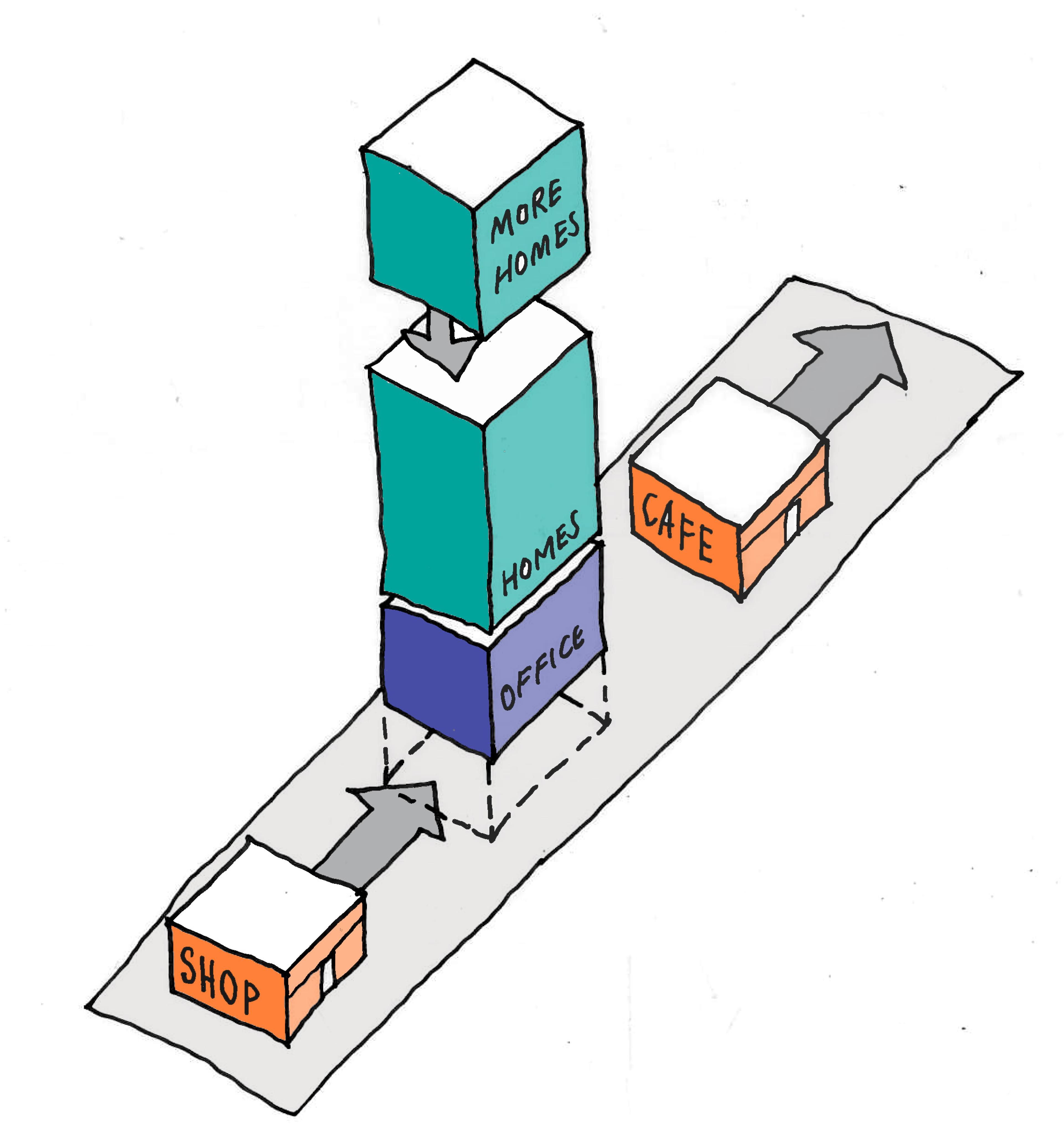

Increasing densities = intense green

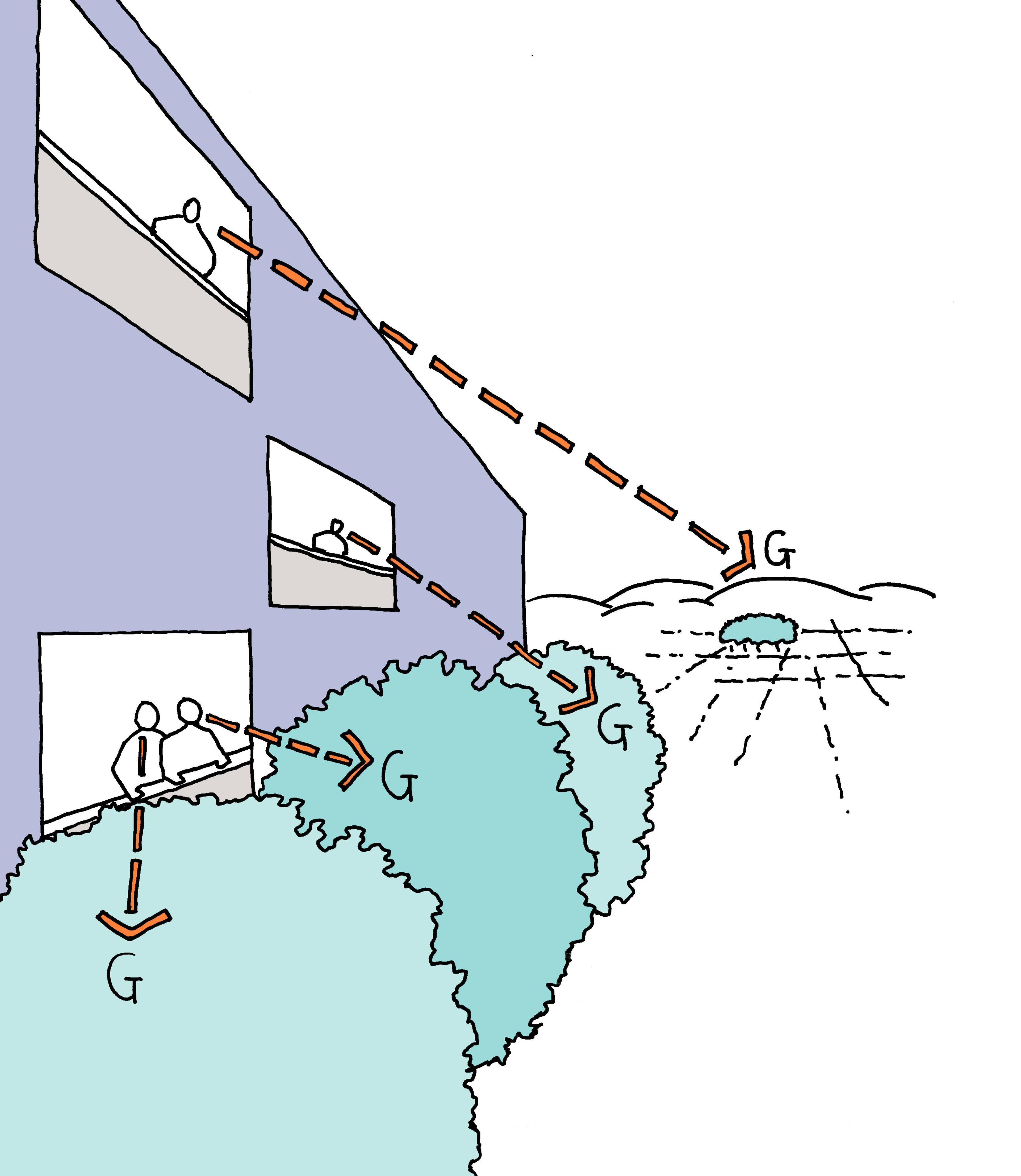

Accommodating an increasing population in higher density urban environments gives the opportunity to intensify the connection to nature. Rather than walking for 20 minutes through a suburban sprawl of tarmac driveways and fenced-off back gardens to reach a park, in dense urban environment accessible green places can be layered throughout. Faced with urban growth and limited land, the Singaporean Government has developed a strategy to transform Singapore from a ‘Garden City’ to a ‘City in a Garden’. This aims to raise the quality of life by creating a city that is nestled in an environment of trees, flowers, parks and rich bio-diversity. Key elements in bringing parks and green spaces right to the doorsteps of people’s homes and workplaces are: roadside greenery, planting and maintaining one million trees and creating a network of ‘park connectors’, green corridors which link between parks. Singapore is also tackling ‘vertical green’ with roof gardens and green balconies becoming the default.

Functional green

Green spaces provide a setting for relaxing or sunbathing, meeting and entertaining, walking, jogging, playing, gardening or bird-watching. In a subliminal way, walking past trees keeps us in touch with the seasons. Modern life is often disconnected from food production and there is value in re-establishing that connection: be it views of wheat fields, grazing animals, tomatoes in allotment polytunnels or lettuces growing in window boxes. Reducing suburban sprawl leaves more land available for food production, protecting that possibility for future generations and as-yet unknown challenges. Trees and planting in cities reduces air pollution and the urban ‘heat island’ effect. It reduces flooding and pressure on drainage infrastructure. Planting provides habitat for animals, birds and insects. It gives character and identity to an area and enhances local pride in the environment.

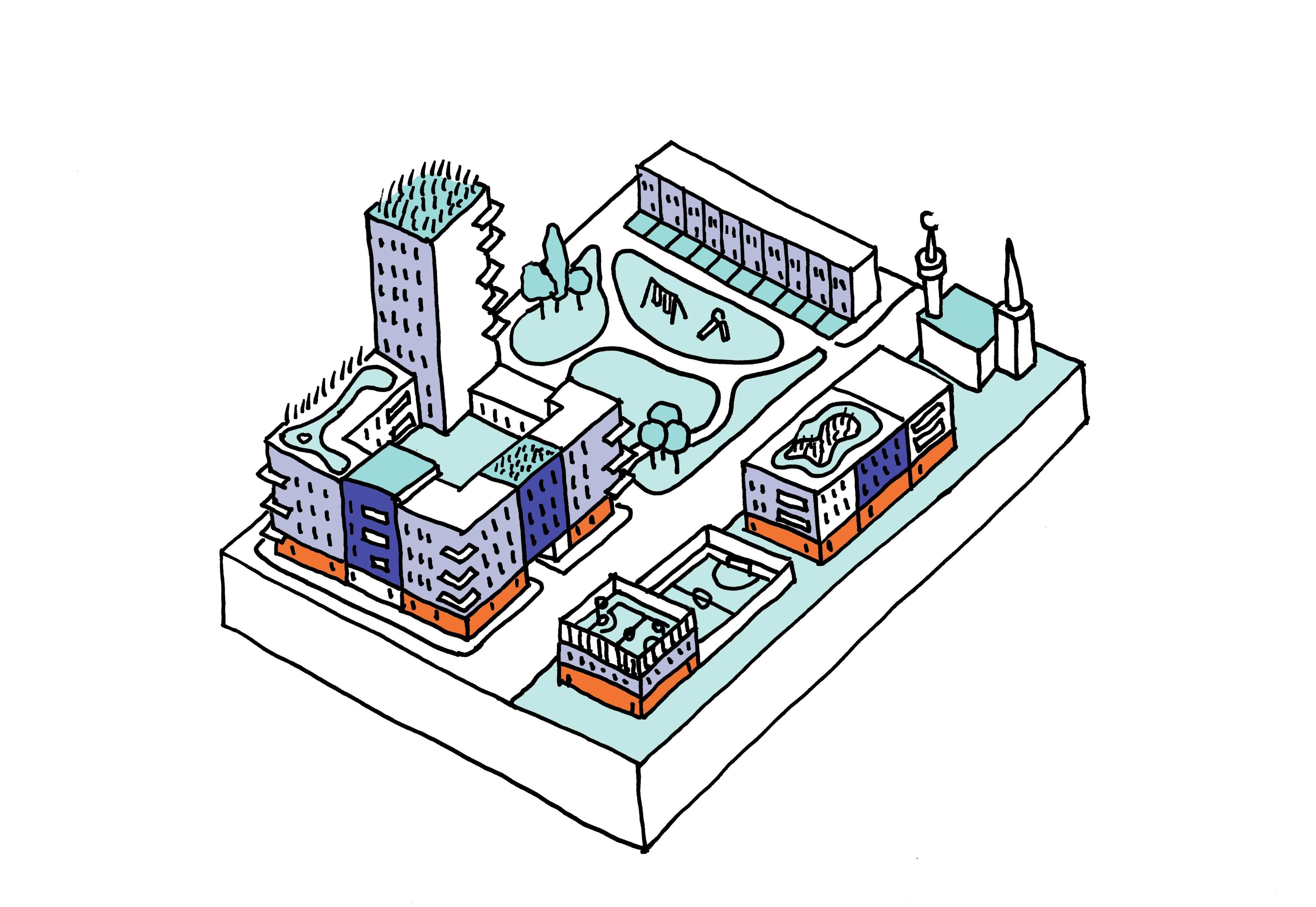

Embedded green

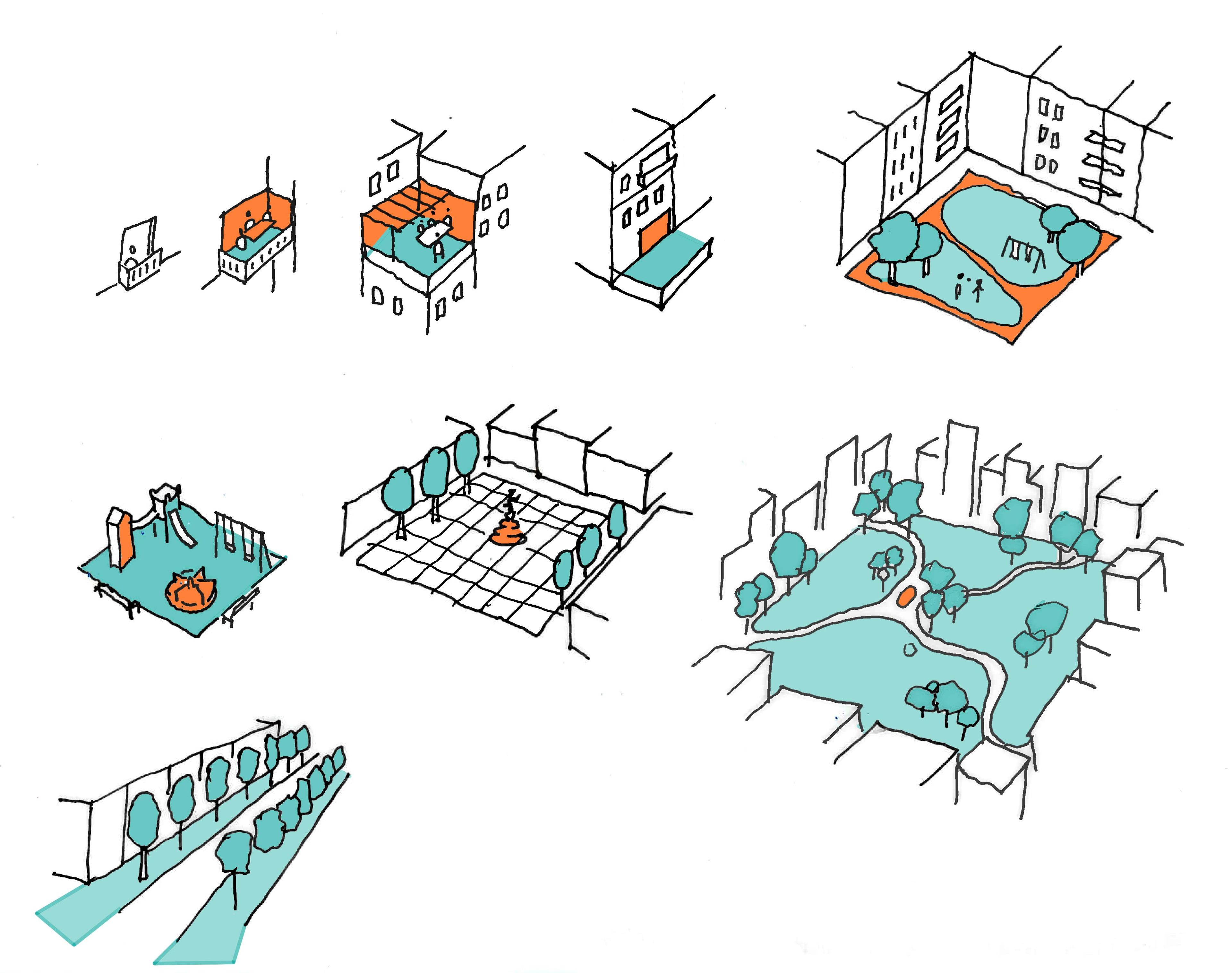

A wide variety of green spaces should be embedded at all scales of the city. The greater the density of the inhabitants, the more parks there should be and the closer they will be to each resident. Filling streets with trees and planted verges is an easy win in terms of visual amenity, environmental benefits and birdsong. Private individual back-gardens are the default British model for families and later life but investment needs to be made in other models in order to maximise value and relevance to a wider variety of households.

Most balconies built today are too small to be valued amenity spaces, usually home to drying washing and bikes. Making balconies large enough to be real useable ‘outdoor rooms’ with space for planting would make apartment-living immediately more appealing to a wider demographic, perhaps reducing the flight of young families to the suburbs. A simple move, such as offsetting apartment layouts on alternate floors so that a double-height outdoor space which is much more bright and airy. Built-in window boxes encourage micro-scale gardening, personal expression and character, giving visual amenity to many. Green and brown roofs play an important role in providing habitats for birds and insects, reducing water run-off, increasing insulation as well as visual amenity, without necessarily having to be accessible useable spaces.

Shared green

Shared private spaces, such as roof gardens or courtyard gardens are very popular in other European countries but not so common in the UK. Allotments or community gardens are being set up in neighbourhood parks and empty sites but these could also be established on roofs or in courtyards of new residential developments. Gardening, composting and play equipment, for example, can be much more effective on a scale bigger than a single household. The key is finding the size of the community where a sense of individual investment, responsibility and defensible space is maintained – easiest with a group of families perhaps. The exploration of semi-private or shared spaces can unlock many opportunities. Commercial units can also provide amenity in a city, such as a plant nursery or urban farm or café garden.

The built environment must always make way for some areas of ‘deep rooted’ green: mature trees or parkland that can become long-term habitats for plants and animals. Embedding nature at all scales and vertical levels of a building, a street and a city brings a vital connection into everyday lives.

This post was extracted from our Vital Cities not Garden Cities report.